Of March and Myth: The Politicizing of Science

Of March and Myth: The Politicizing of Science

Scientific integrity, self-correction, and the public

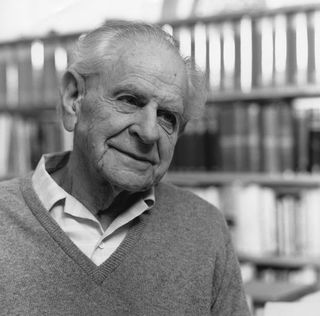

British philosopher of science Karl Popper believed

in the doctrine of falsifiability, i.e., that hypotheses can be tested

and refuted. That is the difference between the scientific method and

other methods of inquiry.

Source: WikimediaCommons.org/Public Domain

To address some of the issues and difficulties within science, the National Academy of Sciences recently sponsored a three-day Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium Reproducibility of Research: Issues and Proposed Remedies, organized by Drs. David B. Allison, Richard Shiffrin, and Victoria Stodden, in Washington, DC. This colloquium brought together international leaders from multiple disciplines, including Nobel-Prize winning researcher Dr. Randy Schekman, its keynote speaker; 28 of these lectures can be retrieved on YouTube.com (Sackler channel.) (For a summary of these outstanding lectures, see Cynthia M. Kroeger’s http://www.bitss.org/2017/04/03/reproducibility-of-research-issues-and-p....) The subject is clearly opportune: Rigor Mortis: How Sloppy Science Creates Worthless Cures, Crushes Hope, and Wastes Billions by science journalist Richard Harris was released recently.

Science journalist Richard Harris explores the crisis in reproducibility in science in his recently published book.

Source: photo by Sylvia R. Karasu, M.D.

Sloppiness also occurs when imprecise language fails in “capturing the science” for the media, says colloquium speaker University of Pennsylvania Professor of Communications Kathleen Hall Jamieson. Without accuracy, scientists are “inviting misinterpretation” and what she calls “narrative infidelity.” Scientists, for example, generate confusion when they write of “herd immunity” as opposed to “community immunity” or when they create the “controversial frame” of a “three-parent baby” when they describe the technique of obtaining genetic material from a cell’s mitochondria, the energy powerhouse of the cell, says Jamieson. She adds, “Mitochondria do not determine parenthood.”

Jamieson, though, is loath to call the existing scientific narrative a crisis. Rather than the accepting the narrative, “Science is broken,” Jamieson prefers to view science as “self-correcting,” (Alberts et al, Science, 2015) just as Karl Popper had emphasized years earlier. Colloquium organizer Shiffrin also takes issue with the use of “inflammatory rhetoric” that merely increases the public’s skepticism and undermines its trust in science. Shiffrin noted that since so much of science is exploratory, with a need for “successive refinement,” it does not always lend itself to reproducibility. Researcher John Ioannidis, writing recently in JAMA (2017) acknowledges the importance of reproducibility and what we can learn when results cannot be replicated; he also appreciates, though, the complications that can arise from “unanticipated outcomes” in “complex and multifactorial” biological systems that can interfere with reproducibility.

One of the difficulties in reproducing results is that there are literally hundreds of kinds of bias--systematic errors as opposed to errors by chance-- that can creep, either knowingly or not, into scientific studies. “Science, though, is a bias-reduction technique and the best method to come to objective knowledge about the world,” says organizer Allison, who is a Distinguished Professor, biostatistician and Director of Nutrition Obesity Research Center (NORC) at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “Its validity depends on its procedures but there is always room for improvement,” he adds.

Another type of bias that can occur, as well, is what Allison and his colleague Mark Cope, in their 2010 papers in both the International Journal of Obesity (London) and Acta Paediatrica, call white hat bias, which they define as “bias leading to distortion of information in the service of what might be perceived as righteous ends.” Examples of this kind of bias include misleading and inaccurate reporting of data from scientific studies by “exaggerating the strength of the evidence” or issuing media press reports that distort, misrepresent, or even fail to present the actual facts of the research or do not even mention any caveats or limitations. Cope and Allison note that white hat bias can be either intentional or unintentional and can ‘demonize’ or ‘sanctify’ research. Sumner et al (PLOS One, 2016) for example, note that press releases “routinely condense complex scientific findings and theories into digestible packets” that may produce “unintended subtle exaggerations” when they use simple language. Regardless of which way white hat bias leans, though, it can be “sufficient to misguide readers,” say Cope and Allison.

William Blake's "Newton," 1795, Tate Britain.

Source: WikimediaCommons.org/Public Domain

One of the procedures that scientists are beginning to recognize as a prerequisite for reproducibility and scientific integrity is the need for full transparency and a sharing of data as the default position. “Show your work and share, lessons we all learned in kindergarten,” says colloquium speaker Brian Nosek, a psychology professor at the University of Virginia. Some researchers have now suggested those papers receive a badge, a kind of seal of approval, as an incentive for full disclosure. Cottrell, who supports the idea that peer review in science should no longer be anonymous and calls it an “historical anachronism” (Research Ethics, 2014) has described science as “struggling with a crisis of confidence.”And since young researchers model themselves after the ethical conduct of their mentors, a laboratory’s culture becomes exceptionally important.

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797): "An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump," 1768, National Gallery, London

Source: WikimediaCommons.org/Public Domain

Perhaps there should be. Mistakes in the literature, of course, are not just of academic interest: they can have far-reaching public health consequences. Many parents, for example, were wrongly discouraged from vaccinating their children because of the fraudulent connection between vaccinations and autism that had been published (and later retracted) in the reputable British journal Lancet. In recent years, there is now an organization Retraction Watch that reports on and encourages this self-policing practice.

While scientists are becoming more cognizant of their need to self-police, they are also aware of the need of calling attention publicly to the importance of science. Organizers of the April 22nd March for Science, in 500 cities worldwide, proclaim “Science, not Silence.” While hundreds of thousands of scientists have registered, not all scientists believe the march will accomplish its goal. Coastal geologist Robert S. Young, for example, in a New York Times editorial back in January (1/31/17), thinks the march will politicize science even further and create a “mass spectacle.” Said Young, “We need storytellers, not marchers.”

The main impetus for the upcoming march is the looming threat of a substantial reduction involving billions of dollars in public funding for scientific research in the proposed budget of the Trump Administration. How very different from other administrations. It was, after all, an Act of Congress, signed in 1863 by then President Abraham Lincoln that had first established the National Academy of Sciences, perhaps our nation’s most prestigious assemblage of scientific scholars that now include almost 500 Nobel-Prize winners among its members. How has it now come to this, though, that science needs both its marchers and its storytellers?

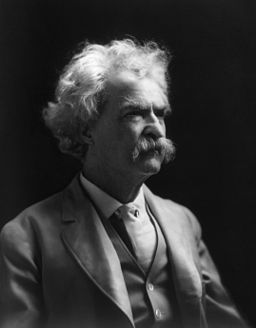

American humorist Mark Twain, back in the 1870s,

attacked science when he spoofed the nonsensical extrapolation of data.

Attacks on science are nothing new.

Source: WikimediaCommons.org/Public Domain

Marches and stories are useful for generating awareness, but they are not enough. Scientists will convince the public and funding agencies of the importance of their science, though, only by their own unrelenting adherence to a culture that consistently fosters self-scrutiny and the value of self-correction. That is the science defined by Karl Popper over fifty years ago.

Karl Popper's classic 1963 book, "Conjectures and

Refutations" in which he writes, "Science must begin with myths and with

the criticism of myths."