What Happens When a Therapist Goes Away

A therapist muses about growth and development and vacations.

According to stereotype,

most psychotherapists go away in August and there is truth in this

one, at least for some of us. Back in the day, therapists did not even

leave a forwarding address, whereas now, many let their patients know

that they are in fact reachable. Hopefully in what is called a good

therapeutic alliance, a patient can trust that his/her therapist has not

dropped off the face of the earth and will return.

What do therapists do on those long vacations? Ideally

recharge, get a break from the strenuous job of keeping one’s patients

firmly and seriously in mind and come back rejuvenated . It is not that

my patients drop out of my thoughts when I go away, but it is that for a

brief time when I am not in my office, my mind gets to wander a bit

more than usual. A capacity for evenly hovering attention, which is one

of the basic tools in the psychotherapist's toolbox can get freed up to

hover over everyday events and activities in ways that can be surprising

and illuminating.

This past August, my temporarily freed up attention turned to birds and some lessons the universe seemed to want to communicate to me in my free time.Coincidentally I had three big bird related experiences (no, not Big Bird!). Each one got me thinking about growth, change, endings and beginnings (all which tend to be ideas which perpetually hover in the back of therapists’ minds).

My first bird lesson was disturbing. I was staying in a house with a porch nestled in the trees. One day, upon returning, I found a dead black bird on the cushioned seat of a porch chair,. It was large, unlike the diminutive multicolored (blue, red, yellow) ones who delightfully populated the dense trees surrounding the porch, or the miniscule hummingbirds who came to sip from a designated humming bird feeder ( I saw at least three which is now my lifetime record).

This avian corpse, lying against the royal blue canvas of a chair shocked me ; its deadness was stark and jarring. Most likely, the bird had flown head first into a plate glass window above the chair, because a mirror was visible through the window which reflected the trees outside the porch. I could see the tiny smudge on the glass where the bird must have struck as it soared for what seemed to be the trees. Flight had become extinction in a moment. There was something sinister about that bird, as if it were an omen or a portent. But of course it was: a dead bird appearing unbidden on a sunny day doesn’t just portend death, it IS death. It is in your face. Always hovering even when out of mind. It reminded me of an experience I had as a college student when I found a dead cat; seeing it occasioned my writing a brief and cryptic poem that I recently discovered. “ A dead cat / is as dead/ as a dead man” .

The second bird experience came on a beach, over which a huge winged silhouette soared above me. A hawk?…no too big, maybe a kite, since it was so flat and streamlined, but no string… an animatronic toy? But no one was holding a remote, the beach was empty. The explanation presented itself on some beach grass behind me; a gigantic bird had suddenly alighted: brown, wings down now, and almost prehistoric in the hugeness of its body. Nothing like the great blue heron whose name denotes its wingspan. A call to the Audubon society clarified that what I had seen was an eagle: an” immature” bald eagle to be exact. They soar flat and streamlined with scalloped wings. From below, the silhouette reads black. They are the largest birds in North America. It’s immature designation, was related to its age, under 5, which can be known since its brown head had not yet turned to the iconic white of our American symbol. Even in its enormity, it turns out that the eagle wasn’t there yet. There is a apparently a before and after, a moment when its brown head turns white and the eagle is mature; it’s clearly not about size, but about developmental timetables. Is that a gradual change or a sudden one? Apparently it happens by transitional molting, each layer of brown on the head lightening over time until a critical threshold is reached and brown becomes white.

But clearly in all maturing, there comes a moment, when

transitions morph into set structures: definitive, no turning back,

hopefully for the better. A temporal threshold gets crossed so that the

eagle becomes its most definitive white-capped self. This is a bit like

human growth and development, What are the ceilings, the benchmarks,

the special somethings that define a settled state of being, or are we

always works in progress? For my patients, I try to help them identify

and move toward certain benchmarks: work, love, a stable sense of identity

and the capacity to sustain on ongoing relationship even when it is

interrupted. It is hard to know what those are for each person when

viewed from a distance; one has to be up close to see the markers of

growth, change and regrouping, and understand how those look for

different individuals.

But clearly in all maturing, there comes a moment, when

transitions morph into set structures: definitive, no turning back,

hopefully for the better. A temporal threshold gets crossed so that the

eagle becomes its most definitive white-capped self. This is a bit like

human growth and development, What are the ceilings, the benchmarks,

the special somethings that define a settled state of being, or are we

always works in progress? For my patients, I try to help them identify

and move toward certain benchmarks: work, love, a stable sense of identity

and the capacity to sustain on ongoing relationship even when it is

interrupted. It is hard to know what those are for each person when

viewed from a distance; one has to be up close to see the markers of

growth, change and regrouping, and understand how those look for

different individuals.

Oddly when one goes away and returns, like from a summer vacation, patients' reactions to the reunion can help tell you where things stand in their emotional landscape and can denote defensiveness or deepening: “I assumed you had forgotten me and would not be here today” ; “ I think I really don’t need therapy since I obviously did fine without you” or ( a sign of progress or stability)

“I kept you in mind when I had a problem” .

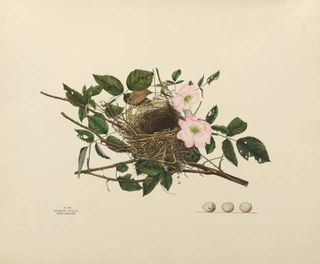

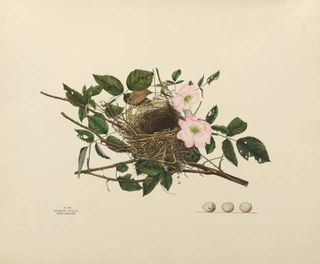

My final bird lesson took place on that same porch later in August. A hanging pot of impatiens became the a site of a bird’s nest. It was not clear to me at first why a small bird kept landing on that plant. When I stood on a chair and looked in, there was an intricate nest and four tiny eggs. Nothing there before when I hung up the plant and then as if by magic, an intricate nest and the eggs. But when did the bird do it? All I witnessed was occasional coming and going, not seeing the many moments that involved building and laying. Moments accumulated to create structures that existed in space, transformed over time. Some time after the eggs appeared, I looked in and thought at first the nest was abandoned, the eggs gone, because all I saw was fluff: mold perhaps? But no, it was a down covering on the heads of the tiny breathing birds. But the mother had not been around at all; had she abandoned the eggs and if so, what was I to do? I turned to ornithology experts on the internet to see how to help. It turns out it is actually illegal to interfere with the nesting patterns of live birds. One has to let nature take its course; since even if one tries to rescue abandoned birds, the job is tireless with feedings every hour requiring strict temperature control, and even then the fledglings rarely survive.

But the mother did come and go with stealth, such that the tiny heads got bigger, the down cobwebs went away; they lived and thrived. Maybe I would get to see them emerge, take flight. What a privilege that would be. But as palpably and invisibly as the babies grew, they slipped out of the nest when I wasn’t looking. They too matured at the critical moment when they could get up and go. They did not die; they developed just like they were supposed to; I missed the turning point…but then again, who asked me?

So the third bird lesson made me think for a moment about my job

and my responsibilities to my patients. One cannot sit on a nest all

day, but ideally therapy is a relationship that functions like a safe

space, a mental nest if you will, in which to incubate a process of

growth and change. If I do my job right, that structured space will

exist in both the patients’ minds and my own, the product of many

moments together, even when we are not sitting in the same room.

So the third bird lesson made me think for a moment about my job

and my responsibilities to my patients. One cannot sit on a nest all

day, but ideally therapy is a relationship that functions like a safe

space, a mental nest if you will, in which to incubate a process of

growth and change. If I do my job right, that structured space will

exist in both the patients’ minds and my own, the product of many

moments together, even when we are not sitting in the same room.

This past August, my temporarily freed up attention turned to birds and some lessons the universe seemed to want to communicate to me in my free time.Coincidentally I had three big bird related experiences (no, not Big Bird!). Each one got me thinking about growth, change, endings and beginnings (all which tend to be ideas which perpetually hover in the back of therapists’ minds).

My first bird lesson was disturbing. I was staying in a house with a porch nestled in the trees. One day, upon returning, I found a dead black bird on the cushioned seat of a porch chair,. It was large, unlike the diminutive multicolored (blue, red, yellow) ones who delightfully populated the dense trees surrounding the porch, or the miniscule hummingbirds who came to sip from a designated humming bird feeder ( I saw at least three which is now my lifetime record).

This avian corpse, lying against the royal blue canvas of a chair shocked me ; its deadness was stark and jarring. Most likely, the bird had flown head first into a plate glass window above the chair, because a mirror was visible through the window which reflected the trees outside the porch. I could see the tiny smudge on the glass where the bird must have struck as it soared for what seemed to be the trees. Flight had become extinction in a moment. There was something sinister about that bird, as if it were an omen or a portent. But of course it was: a dead bird appearing unbidden on a sunny day doesn’t just portend death, it IS death. It is in your face. Always hovering even when out of mind. It reminded me of an experience I had as a college student when I found a dead cat; seeing it occasioned my writing a brief and cryptic poem that I recently discovered. “ A dead cat / is as dead/ as a dead man” .

The second bird experience came on a beach, over which a huge winged silhouette soared above me. A hawk?…no too big, maybe a kite, since it was so flat and streamlined, but no string… an animatronic toy? But no one was holding a remote, the beach was empty. The explanation presented itself on some beach grass behind me; a gigantic bird had suddenly alighted: brown, wings down now, and almost prehistoric in the hugeness of its body. Nothing like the great blue heron whose name denotes its wingspan. A call to the Audubon society clarified that what I had seen was an eagle: an” immature” bald eagle to be exact. They soar flat and streamlined with scalloped wings. From below, the silhouette reads black. They are the largest birds in North America. It’s immature designation, was related to its age, under 5, which can be known since its brown head had not yet turned to the iconic white of our American symbol. Even in its enormity, it turns out that the eagle wasn’t there yet. There is a apparently a before and after, a moment when its brown head turns white and the eagle is mature; it’s clearly not about size, but about developmental timetables. Is that a gradual change or a sudden one? Apparently it happens by transitional molting, each layer of brown on the head lightening over time until a critical threshold is reached and brown becomes white.

Source: James Audubon

Oddly when one goes away and returns, like from a summer vacation, patients' reactions to the reunion can help tell you where things stand in their emotional landscape and can denote defensiveness or deepening: “I assumed you had forgotten me and would not be here today” ; “ I think I really don’t need therapy since I obviously did fine without you” or ( a sign of progress or stability)

“I kept you in mind when I had a problem” .

My final bird lesson took place on that same porch later in August. A hanging pot of impatiens became the a site of a bird’s nest. It was not clear to me at first why a small bird kept landing on that plant. When I stood on a chair and looked in, there was an intricate nest and four tiny eggs. Nothing there before when I hung up the plant and then as if by magic, an intricate nest and the eggs. But when did the bird do it? All I witnessed was occasional coming and going, not seeing the many moments that involved building and laying. Moments accumulated to create structures that existed in space, transformed over time. Some time after the eggs appeared, I looked in and thought at first the nest was abandoned, the eggs gone, because all I saw was fluff: mold perhaps? But no, it was a down covering on the heads of the tiny breathing birds. But the mother had not been around at all; had she abandoned the eggs and if so, what was I to do? I turned to ornithology experts on the internet to see how to help. It turns out it is actually illegal to interfere with the nesting patterns of live birds. One has to let nature take its course; since even if one tries to rescue abandoned birds, the job is tireless with feedings every hour requiring strict temperature control, and even then the fledglings rarely survive.

But the mother did come and go with stealth, such that the tiny heads got bigger, the down cobwebs went away; they lived and thrived. Maybe I would get to see them emerge, take flight. What a privilege that would be. But as palpably and invisibly as the babies grew, they slipped out of the nest when I wasn’t looking. They too matured at the critical moment when they could get up and go. They did not die; they developed just like they were supposed to; I missed the turning point…but then again, who asked me?

Source: Genevieve Jones