A New Big Five for Psychotherapists, Part II

Credit goes to https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/what-doesnt-kill-us/201705/why-being-yourself-is-not-good-advice.

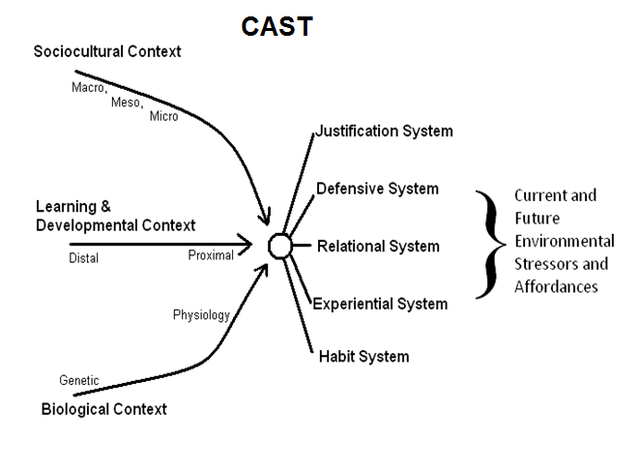

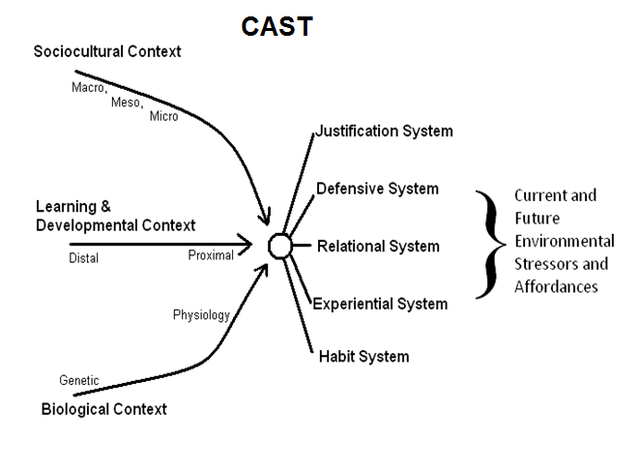

CAST offers psychotherapists a new big five.

CAST is an outgrowth of a new unified theory of psychology (UT) that sets the stage for a unified approach to psychotherapy

(UA). It achieves this by reframing the key insights of the four major

approaches to psychotherapy as emphasizing different systems of human

psychological adaptation.

Part I of this two-part blog series provided the background to understanding how CAST changes the field of psychotherapy.

An analogy to medicine was made and readers were asked to engage in a

thought experiment and imagine medical specialists squabbling over which

biological system was the key to overall health.

We saw how silly it would be if cardiologists debated with those in

orthopedics on whether the circulatory system or the skeletal-muscular

system was central to overall health. The reason this sounded ridiculous

is that we have a relatively unified picture of human biology and

recognize these as different subsystems that connect to a whole.

Part I of this two-part blog series provided the background to understanding how CAST changes the field of psychotherapy.

An analogy to medicine was made and readers were asked to engage in a

thought experiment and imagine medical specialists squabbling over which

biological system was the key to overall health.

We saw how silly it would be if cardiologists debated with those in

orthopedics on whether the circulatory system or the skeletal-muscular

system was central to overall health. The reason this sounded ridiculous

is that we have a relatively unified picture of human biology and

recognize these as different subsystems that connect to a whole.

CAST posits that the current situation in psychotherapy is akin to this thought experiment for the field of medicine. If we look at the major paradigms we see that they have particular elements of psychological adaptation that they tend to focus on. Psychodynamic theory focuses on key relationships and early attachments and how people defend against threatening material. Cognitive therapy focuses on how folks develop verbal interpretations, expectations, and attributions for who they are and how the world works. Behavioral therapies focus on basic learning and how habits are formed via associations and consequences. Humanistic therapies focus on emotions and perceptual experience and the congruence between our true selves and our social selves.

Given that the field is arranged in paradigms, we can step back and ask which one of these insights is central to human psychological health. That is, where do we need to focus our attention to foster human well-being? Is it on habits and lifestyles? Or emotions and emotional functioning? Or human relationships and attachments? Or defenses and coping? Or attributions, beliefs and values, and human narratives? Let’s extend our analogy with our medicine thought experiment, and imagine a conversation between different adherents to these major paradigms.

“The key to psychological health is learning,” says the behavior therapist. “We just need to pair the necessary associations and consequences with the right stimuli and effective functioning in the right environments”.

“No, that is not right. Things are not in and of themselves, but rather are how people interpret them. Thus, we need to look at thoughts, explanations, and attributions, and alter maladaptive thinking patterns into adaptive ones,” says the cognitive therapist.

“Not at all,” says the psychodynamic therapist. “Conscious thoughts just represent the tip of the iceberg. We have to help people gain insight into their defenses and help them understand how their current patterns of being connect to early attachments.”

“You are all wrong,” says the neo-Humanistic emotion-focused therapist. “Emotions are the key. We need to focus on how to coach folks on relating to and processing their emotions in a healthy and adaptive way.”

Instead of being difficult to imagine as was the case when we did this for the medical specialties, this debate is essentially the way the field is currently arranged. The UT argues that the lack of a clear, comprehensive picture of the science of human psychology caused certain gurus (like Freud, Rogers, and Beck) to emerge with “key insights” about human adaptation and develop training models and therapies for dealing with those issues. However, CAST suggests they were only looking at a piece of the puzzle, and if you translate their insights as mapping onto different systems of character adaptation, one can see this in a very clear light.

CAST encourages psychotherapists to ask: What if instead of these ideas being anchored in wholly different paradigms, the truth is closer to the fact that each major paradigm largely focuses on a particular system of psychological adaptation? Specifically, CAST argues that there are five systems of human psychological/ character adaptation. Much of human psychology is understandable through these systems, especially when we consider these systems as existing in biological, learning and developmental, and socio-cultural contexts. Below the five systems are briefly described. The subsequent section makes the direct linkages with the major paradigms.

All of this sets the stage for a radical transformation in how we think about the organization of the field. The implication is that the horse race between the major paradigms in psychotherapy is very much misguided. Instead, we need to step back and see that each paradigm is really just focused on a “piece of the elephant”.

Source: Gregg Henriques

CAST posits that the current situation in psychotherapy is akin to this thought experiment for the field of medicine. If we look at the major paradigms we see that they have particular elements of psychological adaptation that they tend to focus on. Psychodynamic theory focuses on key relationships and early attachments and how people defend against threatening material. Cognitive therapy focuses on how folks develop verbal interpretations, expectations, and attributions for who they are and how the world works. Behavioral therapies focus on basic learning and how habits are formed via associations and consequences. Humanistic therapies focus on emotions and perceptual experience and the congruence between our true selves and our social selves.

Given that the field is arranged in paradigms, we can step back and ask which one of these insights is central to human psychological health. That is, where do we need to focus our attention to foster human well-being? Is it on habits and lifestyles? Or emotions and emotional functioning? Or human relationships and attachments? Or defenses and coping? Or attributions, beliefs and values, and human narratives? Let’s extend our analogy with our medicine thought experiment, and imagine a conversation between different adherents to these major paradigms.

“The key to psychological health is learning,” says the behavior therapist. “We just need to pair the necessary associations and consequences with the right stimuli and effective functioning in the right environments”.

“No, that is not right. Things are not in and of themselves, but rather are how people interpret them. Thus, we need to look at thoughts, explanations, and attributions, and alter maladaptive thinking patterns into adaptive ones,” says the cognitive therapist.

“Not at all,” says the psychodynamic therapist. “Conscious thoughts just represent the tip of the iceberg. We have to help people gain insight into their defenses and help them understand how their current patterns of being connect to early attachments.”

“You are all wrong,” says the neo-Humanistic emotion-focused therapist. “Emotions are the key. We need to focus on how to coach folks on relating to and processing their emotions in a healthy and adaptive way.”

Instead of being difficult to imagine as was the case when we did this for the medical specialties, this debate is essentially the way the field is currently arranged. The UT argues that the lack of a clear, comprehensive picture of the science of human psychology caused certain gurus (like Freud, Rogers, and Beck) to emerge with “key insights” about human adaptation and develop training models and therapies for dealing with those issues. However, CAST suggests they were only looking at a piece of the puzzle, and if you translate their insights as mapping onto different systems of character adaptation, one can see this in a very clear light.

CAST encourages psychotherapists to ask: What if instead of these ideas being anchored in wholly different paradigms, the truth is closer to the fact that each major paradigm largely focuses on a particular system of psychological adaptation? Specifically, CAST argues that there are five systems of human psychological/ character adaptation. Much of human psychology is understandable through these systems, especially when we consider these systems as existing in biological, learning and developmental, and socio-cultural contexts. Below the five systems are briefly described. The subsequent section makes the direct linkages with the major paradigms.

All of this sets the stage for a radical transformation in how we think about the organization of the field. The implication is that the horse race between the major paradigms in psychotherapy is very much misguided. Instead, we need to step back and see that each paradigm is really just focused on a “piece of the elephant”.