Post-Election Vertigo

Post-Election Vertigo

What dislocation can teach us about these unsettling times

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” The famous opening sentence to L. P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between

has not been far from thought since November 9, and it harbors a

potential truth about the soon-to-end Obama era. In the novel, published

in 1953 as much of the world struggled to rebuild after the Second

World War, the protagonist reminisces nostalgically about a happier time

long-predating a range of intensified conflicts, cultural and military.

“If the past is a foreign country, I think it might be invading us right now,”

American historian Charles Richter tweeted on November 10, as the frost began to set on our shivering new era—one featuring widely circulated video of white supremacists celebrating with Nazi salutes at a convention in Washington, D.C. as news of the appointment of Stephen Bannon as White House chief strategist and senior counselor began to filter out. That would be the same purveyor of fake news, conspiracy theories, and white nationalism that propelled Trump’s campaign with a toxic mix of nativism, angry populism, and anti-immigrant resentment. Those currents surfaced months before Trump’s televised promises to imprison his opponent, whom he criminalized by the hour, and his repeated insistence that our current president was the founder of a terrorist organization in the Middle East—all falsities tossed out with blithe disregard for their consequences, here or around the world.

We live in strange times. As the president-elect racks up half-a-dozen serious foreign policy gaffes and blunders in just 48 hours and rejects daily intelligence and State Department briefings, many of us are still reeling from post-election vertigo—the kind of kicked-in-the-gut nausea that stems not from having lost (Clinton in fact won the popular vote by 2.7 million votes and counting, according to the latest updates, with the election turning on a mere 80,000 of them, less than 1 percent of the vote in three critical states, all of them in the process of being recounted or contested). No, the vertigo comes from witnessing a candidate win on a vitriolic, scorched-earth, almost substance-free platform that demonstrated unprecedented, simply brazen mendacity with an eye-watering contempt for truth. The vertigo stems from the fact that the president-elect refused to disavow an endorsement from the KKK—and more than 62 million Americans found a way to look past that, with a seemingly unshakable conviction that the former Senator and Secretary of State was more corrupt than a candidate voicing a stream of demonstrable lies, with no political or government experience other than to have spent months disputing the right of Obama to serve as president. For that, in part, he was awarded the presidency himself.

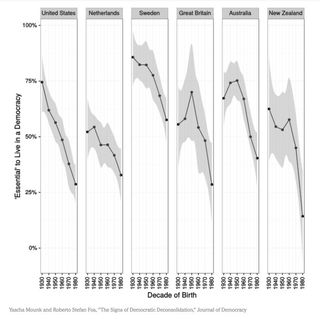

Count me among the bruised and bewildered. At a time when reminders

that Clinton won the popular vote 48.1% to Trump's 46.2% prompt taunts

of being a sore loser, when the pressure to “turn the page” and

normalize these through-the-looking-glass conditions intensifies daily,

it is confounding to hear the president-elect declare two afternoons ago

that he “won by a landslide,” as if the U.S. had morphed overnight into

Russia or Turkey. Even more, at the exact moment the PEOTUS has taken

to singling out journalists for unfavorable coverage on Twitter,

as if they were arraigned before his 16 million followers, reputable

studies point to plummeting declines worldwide of the once-robust

conviction that it is “essential” to live in a democracy, with

skepticism about the need for free elections and a free press most

pronounced among the young but far from insignificant among those older.

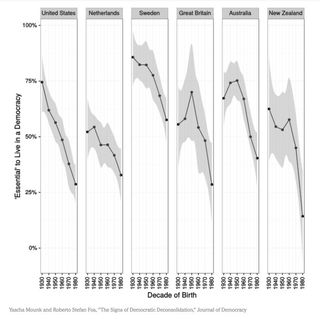

Count me among the bruised and bewildered. At a time when reminders

that Clinton won the popular vote 48.1% to Trump's 46.2% prompt taunts

of being a sore loser, when the pressure to “turn the page” and

normalize these through-the-looking-glass conditions intensifies daily,

it is confounding to hear the president-elect declare two afternoons ago

that he “won by a landslide,” as if the U.S. had morphed overnight into

Russia or Turkey. Even more, at the exact moment the PEOTUS has taken

to singling out journalists for unfavorable coverage on Twitter,

as if they were arraigned before his 16 million followers, reputable

studies point to plummeting declines worldwide of the once-robust

conviction that it is “essential” to live in a democracy, with

skepticism about the need for free elections and a free press most

pronounced among the young but far from insignificant among those older.

Three years before L. P. Hartley started calling the past a foreign country, the psychoanalyst Octave Mannoni wrote a book about the experience of dispossession—about being lost, untethered from one’s native land, or just from daily habits and bearings. “Dislocation,” he observed, “does the job of analysis.” It wrenches us into such a state of confusion and disorientation that familiarity disappears and can’t quite be put back the way it was before. The analogy with Hartley’s past as “foreign country” both haunts and persists because the French term Mannoni used for “dislocation,” dépaysement (literally: being out of, or exiled from, one’s own country) stems from the condition of being dépaysé: adrift, out of one’s element, strange to oneself.

Such states are never enjoyable. They are wrenching, maddening, potentially infused with despair. But they can also, Mannoni argued, be grounds for sharper perception and vigilance, more effective and targeted action, even greater resilience in the teeth of opposition. They can teach us how to fight back honorably and strategically, in the service of facts and respect for truth. They can also show us how to protect the things we admire and love—ideals and practices such as tolerance, pluralism, and respect for facts, reason, and the rule of law that are daily more fragile and, in the coming weeks and months, will be tested severely. Under the new administration, in our new upside-down world, they risk being distorted beyond all recognition.

“If the past is a foreign country, I think it might be invading us right now,”

American historian Charles Richter tweeted on November 10, as the frost began to set on our shivering new era—one featuring widely circulated video of white supremacists celebrating with Nazi salutes at a convention in Washington, D.C. as news of the appointment of Stephen Bannon as White House chief strategist and senior counselor began to filter out. That would be the same purveyor of fake news, conspiracy theories, and white nationalism that propelled Trump’s campaign with a toxic mix of nativism, angry populism, and anti-immigrant resentment. Those currents surfaced months before Trump’s televised promises to imprison his opponent, whom he criminalized by the hour, and his repeated insistence that our current president was the founder of a terrorist organization in the Middle East—all falsities tossed out with blithe disregard for their consequences, here or around the world.

We live in strange times. As the president-elect racks up half-a-dozen serious foreign policy gaffes and blunders in just 48 hours and rejects daily intelligence and State Department briefings, many of us are still reeling from post-election vertigo—the kind of kicked-in-the-gut nausea that stems not from having lost (Clinton in fact won the popular vote by 2.7 million votes and counting, according to the latest updates, with the election turning on a mere 80,000 of them, less than 1 percent of the vote in three critical states, all of them in the process of being recounted or contested). No, the vertigo comes from witnessing a candidate win on a vitriolic, scorched-earth, almost substance-free platform that demonstrated unprecedented, simply brazen mendacity with an eye-watering contempt for truth. The vertigo stems from the fact that the president-elect refused to disavow an endorsement from the KKK—and more than 62 million Americans found a way to look past that, with a seemingly unshakable conviction that the former Senator and Secretary of State was more corrupt than a candidate voicing a stream of demonstrable lies, with no political or government experience other than to have spent months disputing the right of Obama to serve as president. For that, in part, he was awarded the presidency himself.

Source: Journal of Democracy

Three years before L. P. Hartley started calling the past a foreign country, the psychoanalyst Octave Mannoni wrote a book about the experience of dispossession—about being lost, untethered from one’s native land, or just from daily habits and bearings. “Dislocation,” he observed, “does the job of analysis.” It wrenches us into such a state of confusion and disorientation that familiarity disappears and can’t quite be put back the way it was before. The analogy with Hartley’s past as “foreign country” both haunts and persists because the French term Mannoni used for “dislocation,” dépaysement (literally: being out of, or exiled from, one’s own country) stems from the condition of being dépaysé: adrift, out of one’s element, strange to oneself.

Such states are never enjoyable. They are wrenching, maddening, potentially infused with despair. But they can also, Mannoni argued, be grounds for sharper perception and vigilance, more effective and targeted action, even greater resilience in the teeth of opposition. They can teach us how to fight back honorably and strategically, in the service of facts and respect for truth. They can also show us how to protect the things we admire and love—ideals and practices such as tolerance, pluralism, and respect for facts, reason, and the rule of law that are daily more fragile and, in the coming weeks and months, will be tested severely. Under the new administration, in our new upside-down world, they risk being distorted beyond all recognition.